News

While the NHL denies CTE link, another former hockey player is diagnosed

According to official statements from the National Hockey League (NHL), there is absolutely no link between the repetitive hits and crashes in hockey and the development of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). But, the family of former hockey star Jeff Parker would beg to differ.

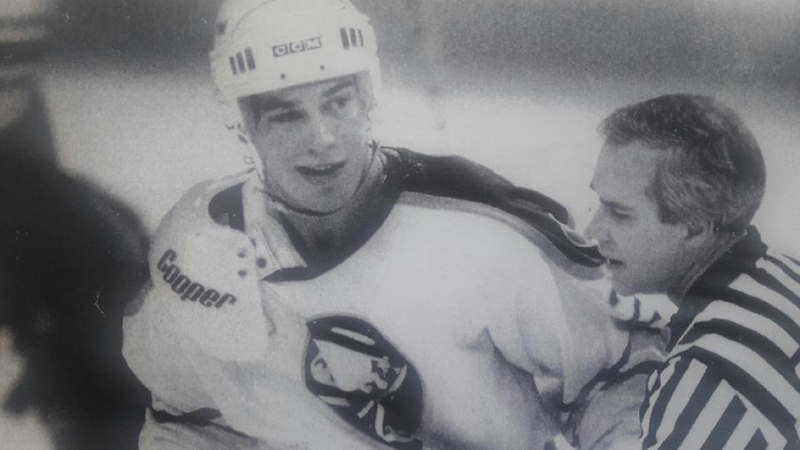

Parker, who died last September at 53 years old, was diagnosed with CTE recently. His family believes this is the result of his years on the ice. In particular, they note it was a series of frightening concussions sustained just 15 days apart that ended his professional hockey career.

The news of his diagnosis during a post-mortem autopsy was no surprise to the Parker Family. They had already come to the same conclusion based on Jeff’s increasingly difficult behavior.

“I knew it all along — when he was late for his brother John’s wedding, when he went to the wrong place for a TV interview, when he would come to my house and go down in the basement because he needed to be in a dark place,” Jeff’s brother, Scott Parker told the Associated Press.

The story is undeniably tragic, but it is hard not to feel a bit of déjà vu. Similar stories were increasingly common approximately a decade ago, as the NFL tried to deny any link between football, repetitive head trauma, and long-term brain disease.

The football league held this stance for years, until the evidence was too overwhelming to deny any longer. Now, it is widely recognized that football players face a uniquely high risk for developing CTE in their lives because of the hundreds or potentially thousands of hits to the head they accumulate throughout their career.

Despite all this, the NHL is still clinging to the perception that the sport – known for its violent collisions and on-the-ice fights – is entirely safe for the brain.

According to the New York Times, Parker is the seventh former NHL player to be diagnosed with CTE after their death. The others are Reggie Fleming, Rick Martin, Bob Probert, Derek Boogaard, Larry Zeidel, and Steve Montador.

Parker’s condition was diagnosed at Stage 3 chronic traumatic encephalopathy, characterized by memory loss and impulsivity.

“It was fairly advanced, and we called it Stage 3 because it was significant,” said Dr. Ann McKee, chief of neuropathology at the V.A. Boston Healthcare System and professor at Boston University’s School of Medicine, where she is director of the CTE Center.

As common among these more severe cases, the disease had spread throughout a significant area of Parker’s brain, but was particularly prominent in the medical temporal lobe. McKee describes this region as “very important areas for memory and learning.”

Parker’s diagnosis places hockey as the sport with the second highest number of CTE diagnoses in former players (with football leading the pack by a large margin). One has to wonder just how many more diagnoses it will take for the league to acknowledge the risks for CTE and take actual steps to protect their players – instead of sticking their heads in the sand.