News

Tricking Baseline Concussion Testing May Easier Then Thought

Source: UPMC Sports Medicine

One of the biggest tools schools and sports organizations have been using to identify concussions may not be as fool-proof as previously believed according to a new study from researchers at Butler University.

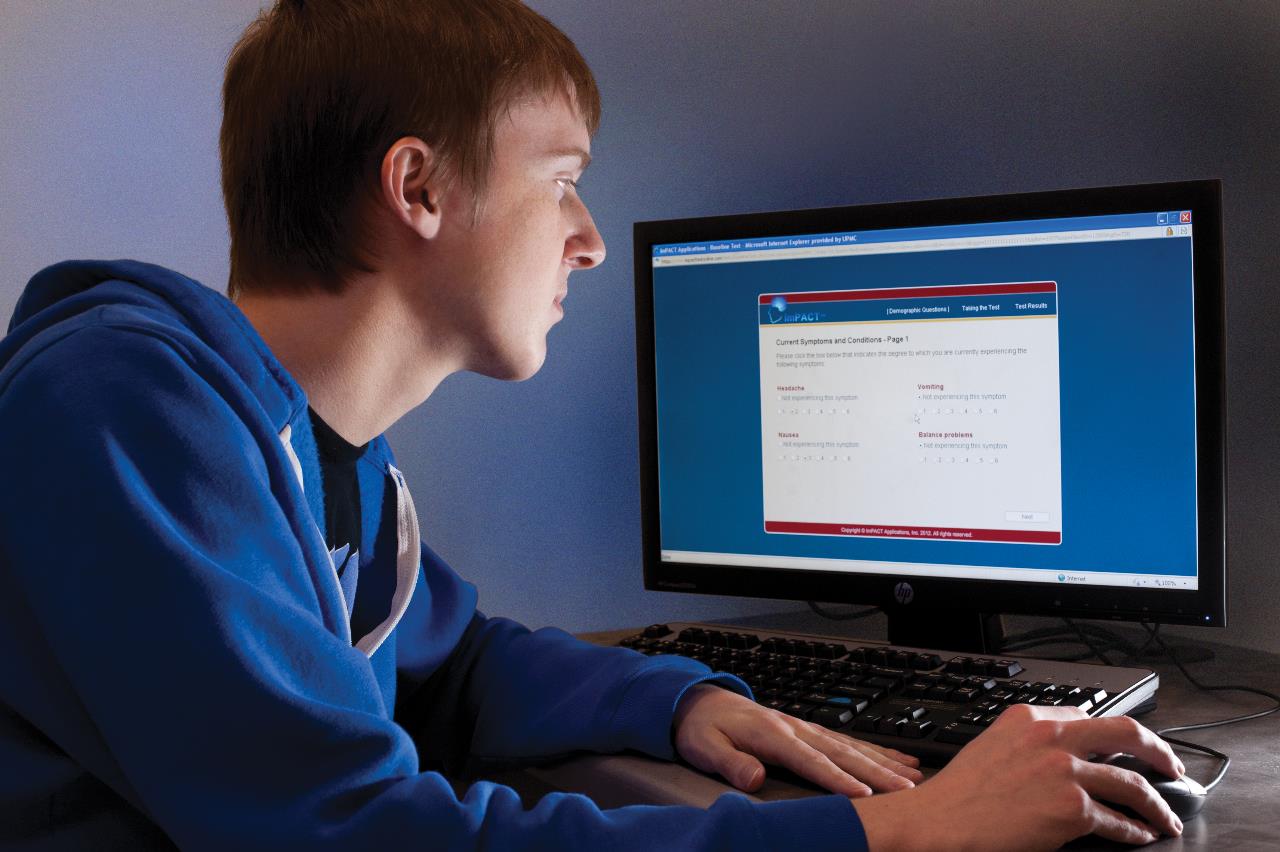

Over the past years, teams and organizations have been adopting the Immediate-Post Concussion Assessment and Cognitive Test, better known as the ImPACT test. This involves baseline testing at the beginning of the season, which can be later used as a point of comparison when testing potentially injured individuals.

Unfortunately, purposefully failing the baseline test can make it nearly impossible to assess a concussion later on. Even worse, the new research indicates that purposely “sandbagging” the test without being detected is not as difficult as previously measured.

In fact, approximately half of takers who purposefully underperformed on the ImPACT test went undetected, allowing them to potentially go undetected if they experienced a concussion during the season.

According to ImPACT Applications, the company who makes the exam, the test has been administered more than 12 million times since 2002.

While the ImPACT test is largely used to examine athletes, the company also markets a pediatric version of the assessment for general examinations.

In the computerized version of the test, participants are asked to answer word, design, color, and matching questions designed to evaluate the brain’s functioning. A similar version of the test is then administered after a potential brain injury.

It is already well-known that a significant number of athletes at both the professional and school-level try to work around concussion assessments. One study found that nearly a third of athletes admitted they did not give “maximal effort” on concussion assessments.

“Anyone who works with the concussed clinically knows there are a lot of people who purposefully sandbag the baseline test and a lot of people don’t get caught,” said Amy Peak, one of the study’s authors and director of undergraduate health science programs at Butler. “I would hear in the community and hear all these athletes tell me, ‘I sandbagged mine, everybody sandbags it.’ ”

Past research indicated that the ImPACT test was uniquely able to weed out sandbaggers. One such study, cited by ImPACT in its “Administration and Interpretation Manual” indicated the test could identify 89% of those who purposefully underperform on the test and invalidates their scores – leading to a retake of the baseline assessment.

The test is designed with five indicators meant to identify any irregularities or sandbaggers.

However, Butler’s study, done in collaboration with Indiana University medical student Courtney Raab, found that only two of the built-in indicators detected more than 15% of the test takers attempting to trick the assessment. Instead, the team found that half of test subjects were able to sandbag the test without being identified without being coached.

“If you believe the built-in invalidity indicators in this test are going to flag the people who are flunking on purpose, they’re not,” Peak said while presenting the findings at the American Academy of Neurology Sports Concussion Conference in Indianapolis this month.

In the study, Peak recruited 77 volunteers. Of those, 40 were randomly chosen and told to purposely sandbag the test. The rest were told to take the test as normal and try their best.

As expected, none of the participants told to take the test as normal were flagged by the system. But, 20 of the 40 people told to fail the test were not flagged by the system either.

The best way to fight against purposeful sandbagging, according to Peak and Raab is to ensure test proctors – typically a team or school’s athletic trainer – work to reinforce the importance of the test and the consequences of repeated head injury.

Athletic trainers, in particular, have a unique position that allows them to suss out sandbaggers because they typically know the test takers personally and can recognize when scores don’t match a test taker’s abilities in the classroom or on the field.

“Once you know the individual, that should give you a strong gut feeling,” Peak said, “Especially in colleges, these trainers know athletes well. They should be able to tell if something doesn’t look right.”